Spooky Marshall County

The following tales are just a taste of spooky Marshall County. Most of the stories are told as they were written long, long ago.

“The neighborhood two miles east of Lapaz is all stirred up over a ghost story, which is vouched for by a number of persons to be fact. Millian Crum and Nathan Crothers were passing the U.B. church in the Berger vicinity several nights ago, and a figure in a white shroud appeared in front of the church and waved its arms. The movement of the white object also frightened their horse, which ran some distance before the animal could be stopped. Charles Charleston who passed the church at an early hour in the morning also claims to have seen a ghost. The story has caused no little talk in the neighborhood. Samuel Thomas who is not afraid of ‘fire or brimstone’ proposes to investigate the affair and will visit the place with a party of men on Saturday night. Mr. Thomas is of the opinion it is a joke being played by some boys to create a sensation and will make an effort to capture the ghost.” From The Bremen Enquirer, May 11th, 1900.

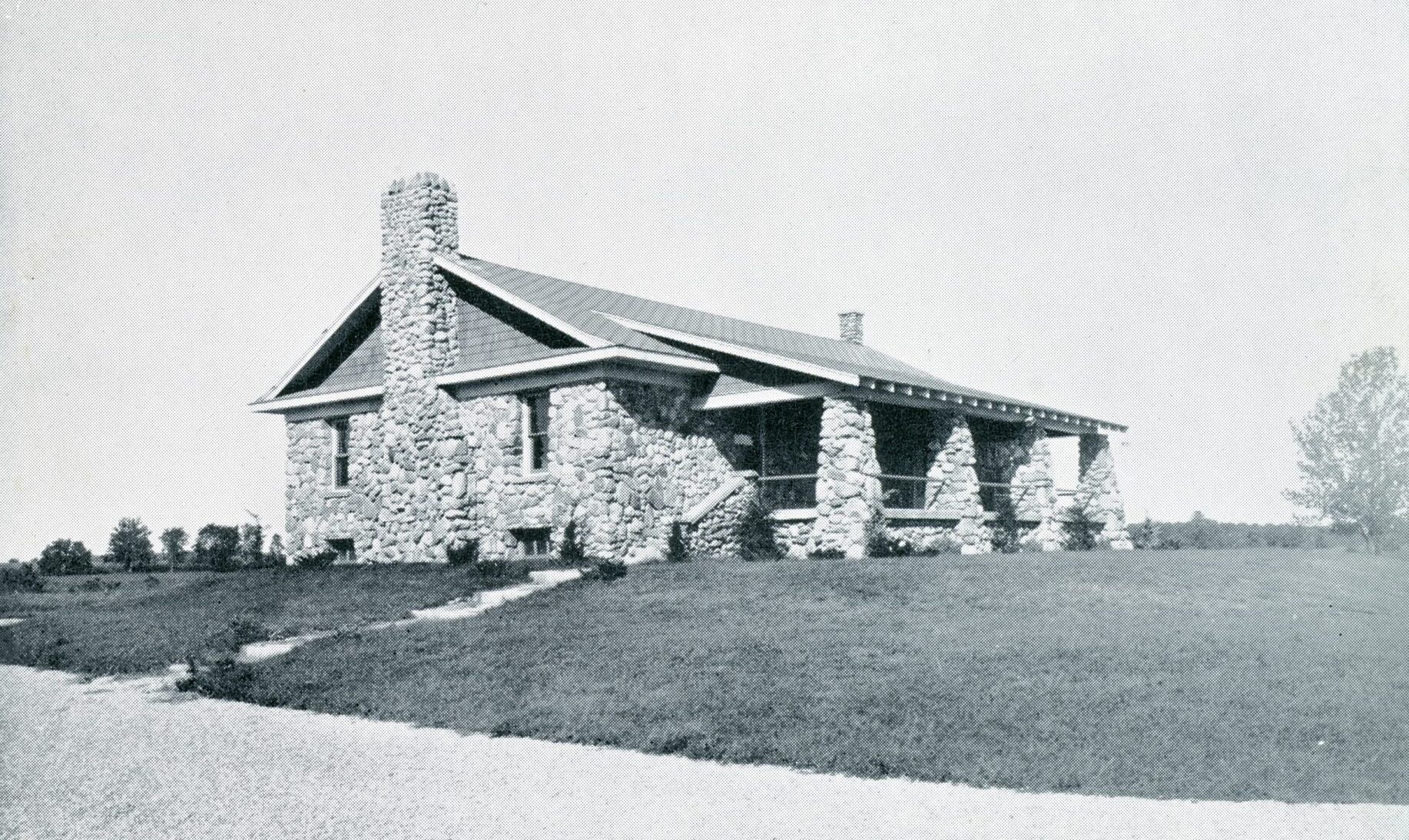

The Higbee Corner Tavern maintained a good reputation. No doubt there was drinking there, and many intoxicated travelers stopped there, but that did not make a place tough in those days. However, the Thompson Tavern did not have a good reputation and was deserted by the time the Higbee Tavern became popular. It was then known as the “Haunted House.” The story is told that when this old tavern was deserted, cattle and pigs used to roam at will in and out of the open doors. One stormy night the pigs had taken refuge in the old building. Two men were passing there that night, and the one who was the least drunk dared the other one to go into the “Haunted House.” With much bravado, increased by the stimulant which they had had, they reeled in through the open door and stumbled over the pigs. The disturbed pigs made so much noise that the intruders started to run, to get away from the “ghosts,” and never stopped until they reached the Higbee Tavern. Written in 1940 in a memoir by Francis Emerson.

The September 1, 1910, issue of The Plymouth Democrat reported that Henry Kelver had a “thrilling experience” on Dixon Lake. He was in the middle of the lake when he saw a dark looking object in the distance approaching his boat. “The water parted into waves on either side of the object as it came nearer…its head looked like that of a big black dog and its eyes snapped ferociously. Just below the blue water of the surface was a big black form, about the size of a wheelbarrow and there seemingly were a hundred pairs of legs wiggling and paddling beneath it. Within two or three rods of the boat the monster turned, dove and disappeared.”

“A terrible murder was committed two miles south of this place on Sunday night last. The circumstances that led to the horrible deed were about as follows: About 4 o’clock Sunday afternoon two men, aged about 30 years, called at the house of Mr. Mikel Hisey and requested to stay until after the rain, which was falling. After sitting in the house about an hour they started to leave. One of the men was of medium size and tolerably well dressed, and the other larger and very rugged. Mr. Hisey thought no more about them until in the morning in passing an old house used for a stable, he heard someone groaning, and going in and up on the loft, where he had some hay, he found the better dressed man with three gashes cut in his head through the skull, and the brains oozing out. The man had been stripped of pants and coat and left with nothing on but shirt, vest, and boots. The boots were both made for one foot. The instrument used to accomplish the deed was a cutter from a shovel plow. Medical aid was summoned, but nothing could be done for the man. He was beyond help, and, of course, could not speak to tell of the deed. He died during the day; nothing being left by which he could be identified. His companion no doubt had done the deed. It is supposed the murderer took the train at Argos, going south, as a man answering the description, with black pants too short by several inches, was seen getting on the train in the morning. Mr. Hisey thinks they were carrying a small bundle when at his house. All possible steps are being taken to secure the arrest of the murderer.” From the October 2, 1873, Plymouth Democrat.