Entertainment in the Good Old Days

Long before the entertainment overload of today, Marshall County youth had some interesting ways of creating their own fun. They did have theaters, but much of the time, they relied on simple things dictated by what was at hand, our location and the weather. The following collection is from oral histories in our archives.

Performing Arts

“The Orpheum Theater cost a nickel. It was on, oh, just a little way north of Washington Street on Michigan, where the old Orpheum was. They’d have Saturday afternoon matinees for a nickel. And there were shows, there were some outside shows, tent shows, down on, in the area where the fire station parking lot is now, on the corner of LaPorte and Center Street, just a block south of the library.” Stanley Brown

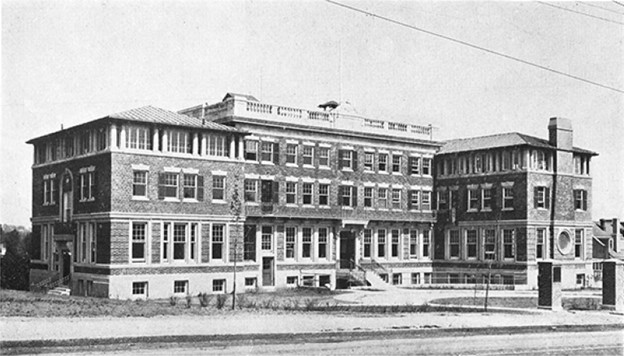

The Orpheum Theatre in Plymouth, Indiana.

“About playing piano for the silent movies in Plymouth – When I played, I played for the big sum of $3.00 a week, and six nights a week, 7:00 to 10:00 on the weekdays. On Saturday nights it was seven ‘til 11:00, and it was nickel shows, you know, every night, and we had songs. They used to have sing-a-song, you know, and the words, and the little ball would bounce up. And I’d play for that, and that song came along with the film. We had a girl or boy, a singer, and that was all they done, was sing that song at every show.” Etta Steiner

“We had travelling stage shows quite often. They would come and book a week’s time at the opera house.” Beatrice Pickerl

Seasonal Fun

“We had sleigh ride parties and bobsled parties. And on the bobsled parties whenever you went under a streetlight, you got to kiss the girl that you were with. There were not very many streetlights in those days.” Morris Cressner

Sleighing party for city kids, 1916.

“You’d listen the first morning of cold weather, the first snowy, icy morning, see if you could hear Uncle J. T.’s sleigh bells. Uncle J. lived north of town (Argos), probably a mile and a half, might be two miles. And Uncle J. always had his sleigh out first, and he was the only person that the children of the town, that I knew best, could go riding with without running home and asking their parents. But if Uncle J. had his sleigh, we would go with him, and he’d take us a very nice fast ride down to the Nickel Plate Railroad.” Beatrice Pickerl

The Joy In the Everyday

“Used to be a train come in and my brother and different ones would walk over to Tyner to see it come in, and I believe every Friday or Saturday night from South Bend. That was a big thing. It was called the Cannonball. It would come in at 10:00. And the depot was right below our house here. That was their entertainment, was to come and watch the Cannonball.” Ray Jacobson

“They had the old [gas] street lights in Plymouth, and a man had to go around with a long pole and pull them down and light them by hand. He’d put a match to them and put them back up. Kids at night, after they got that light lit – one of our forms of fun was catching bats. There used to be a lot of bats around. They’d fly around those lights. We’d throw our caps up and every once in a while, we’d get a bat in them.” Stanley Brown

Bourbon street scene with gas street light.

Social Get-Togethers

“What progressed into hockey we called shinny. We used sticks and tin cans.” Homer Riddle

“We used to have spelling bees at the school house. And we’d spell, and the old people as well as the young would be in that, don’t you know. They’d all stand up and then when you missed a word, you sit down, and then the last one that stayed up got a prize.” Alta Listenberger

“We used to have box socials. The girls would take a box of food and then they’d auction it off and the boy that bought it, he wouldn’t know whose he’s buying, don’t you know, because they’d decorate these boxes up beautiful. And then the boy that bought them would eat with the girl. He wouldn’t know ‘til he got the box unless she’d tell him or, you know, the girl he liked would tell him which was her box. But otherwise they kept that a secret. Sometimes you’d eat with an old man. I’ve ate with old men, you know, some old farmer, instead of eating with the boy I wanted to eat with because he paid the most for the box.” Alta Listenberger

Learn more about everyday life in Marshall County by visiting our Museum!