Fun Facts about Valentine’s Day

Feature Image. An assortment of Valentine’s cards from the Museum collection.

The iconic cupid of Valentines Day, with a cherubic face and angelic wings, began as the Greek god, Eros. He was the son of Aphrodite, the goddess of love and procreation. Cupid is known to shoot two types of arrows, one to cause people to fall in love, and one to make them hate each other. We’ve compiled some fun and interesting Valentine’s Day info from the web!

Food Is the Way to the Heart

Candy hearts began with a Boston pharmacist Oliver Chase. He invented a machine that produced small medical lozenges for the throat. When he saw how popular they were, he turned them into candy with cute messages on them.

Of course, chocolate is a huge part of Valentine’s Day now, but it has a sad beginning. Physicians in the old days would recommend chocolate to people suffering from a broken heart or pining for a lost love. It was Richard Cadbury, a British chocolatier, who invented the first chocolate box. Always the businessman, he realized that he could capitalize on Valentine’s Day by producing chocolate boxes and marketing them as something to be given to your sweetheart.

Valentine’s Day is not celebrated the same way all over the world. In Japan for instance, on February 14th, women give gifts and chocolates to their male companions. The men don’t reciprocate until March 14, which is known as “White Day.” On Valentine’s Day in England, women used to place five bay leaves on their pillows. This was done with an aim to bring dreams of their future husbands. In Norfolk, England, Jack Valentine acts as a Santa for Valentine’s Day. Children anxiously wait for the treats, though they don’t get to see Old Father Valentine. In many places, Valentine’s Day is also celebrated as the beginning of spring.

People Associated with Valentine's Day

Venus, the goddess of love, adored red roses, making them a perfect symbol to express love for another person. To the Victorians, the deeper the rose color, the deeper the passion. A white rose would have been appropriate for a young girl or woman who had not felt passionate love. In a contradiction, the white rose symbolized soul-deep love and marriage. White roses are often referred to as “bridal roses.”

Saint Valentine, for whom the holiday is named, defied the emperor Claudius of Rome. Marriage was outlawed because the emperor believed single men made better soldiers. Saint Valentine performed weddings in secret in defiance of the unfair law. Pope Gelasius later declared the Valentine’s Day holiday in 498 A.D.

Another fun fact. Penicillin, the world’s first antibiotic and one of the greatest scientific discoveries, was introduced to the world on Valentine’s Day. Alexander Fleming was the Scottish physician-scientist who was recognized for discovering penicillin. The simple discovery and use of the antibiotic agent has saved millions of lives and earned Fleming – together with Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, who devised methods for the large-scale isolation and production of penicillin – the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine.

Sharing Love Notes

In one ironic twist, Alexander Graham Bell applied for the patent to the telephone on February 14th, 1876, never imagining that it would become the biggest medium for sending Valentine’s Day greetings almost 150 years later.

As for sending cards, Valentine’s Day is second only to Christmas in the number of cards sent around the world. Today, most cards are mass-produced and generally the selection is pretty sparce by the 14th. Artist Esther Howland was one of the first American printers to start producing Valentine’s Day cards beginning in the 1850s. Ornate cards trimmed with lace became treasured mementos, but why lace? Lace is commonly used in making bouquets of roses and in other items during Valentine’s Day. The word ‘lace’ comes from the Latin word ‘laques’ which means to snare or trap a person’s heart. Isn’t that fitting?

We sign our valentines with Xs and Os to send kisses and hugs. This is not the letter X’s original purpose. In medieval times, most people could not read or write. If a need arose to sign their name, most would simple mark an X. To show affection and loyalty, the writer would kiss the X on the paper before sending.

The often-heard term “wear your heart on your sleeve” began with an old custom. People would pick a name out of a bowl to see who their valentine would be. They would then pin the paper to their sleeve for everyone to see.

The oldest known valentine still in existence today is perhaps a poem written in 1415 by Charles, Duke of Orleans, to his wife while he was imprisoned in the Tower of London following his capture at the Battle of Agincourt. A lot of his poetry was not so cheerful as he wasn’t released until 1440, and the poem below was written after his wife died.

Let men and women of Love’s party

Choose their St. Valentine this year!

I remain alone, comfort stolen from me

On the hard bed of painful thought.

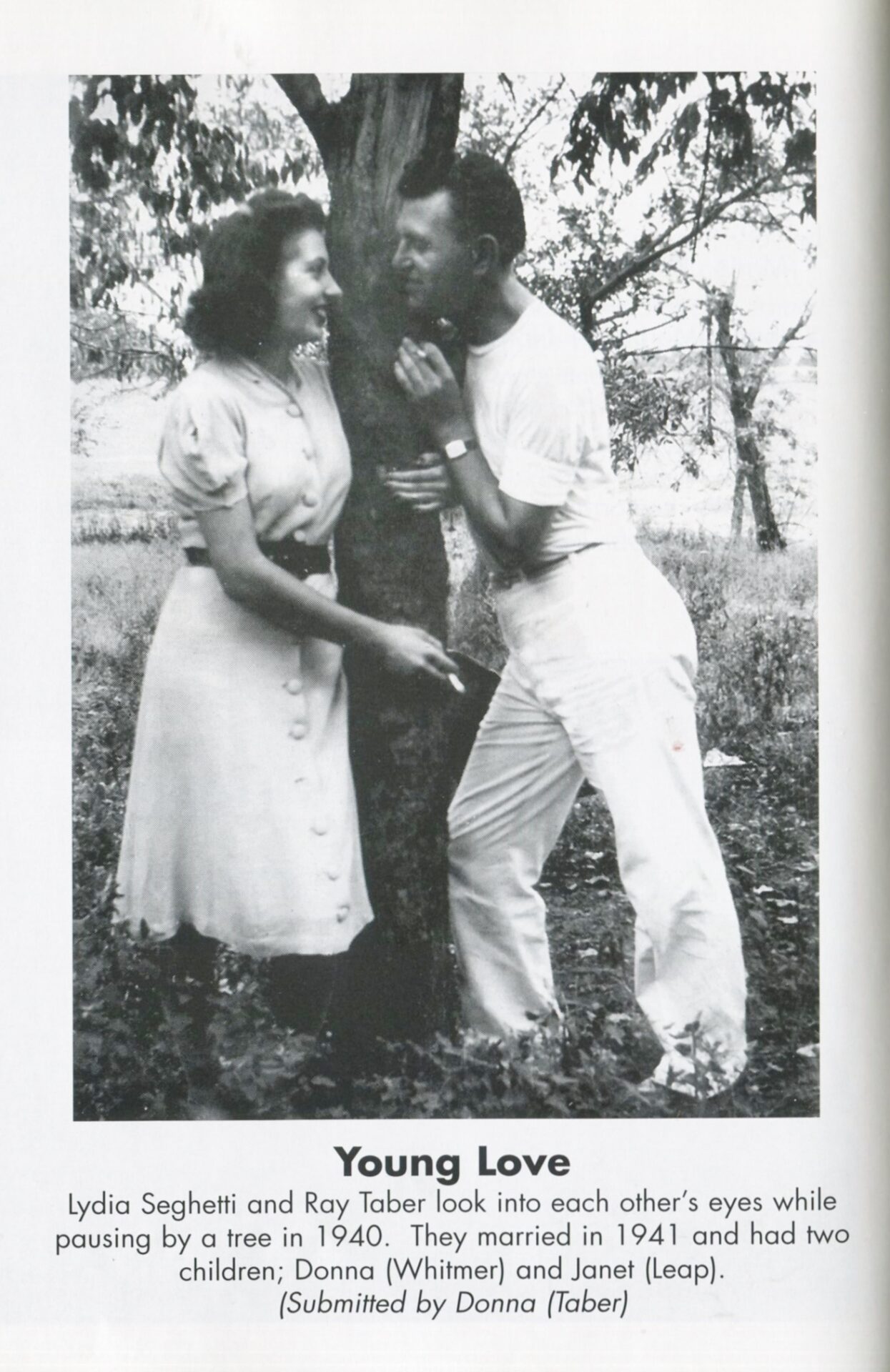

Lyda Seghetti and Ray Taber leaning agaist tree, ca. 1940. Featured in Plymouth Remembered, page 80.

The Museum is home to a large selection of antique and vintage valentines, although not currently on display. You can still come see our treasures, perhaps as a lovely museum date! The Museum is open from 10 until 4 from Tuesday through Saturday at 123 N. Michigan St., Plymouth. For more information, call 574-936-2306.