Betty Jane Smith: A Culver Tragedy

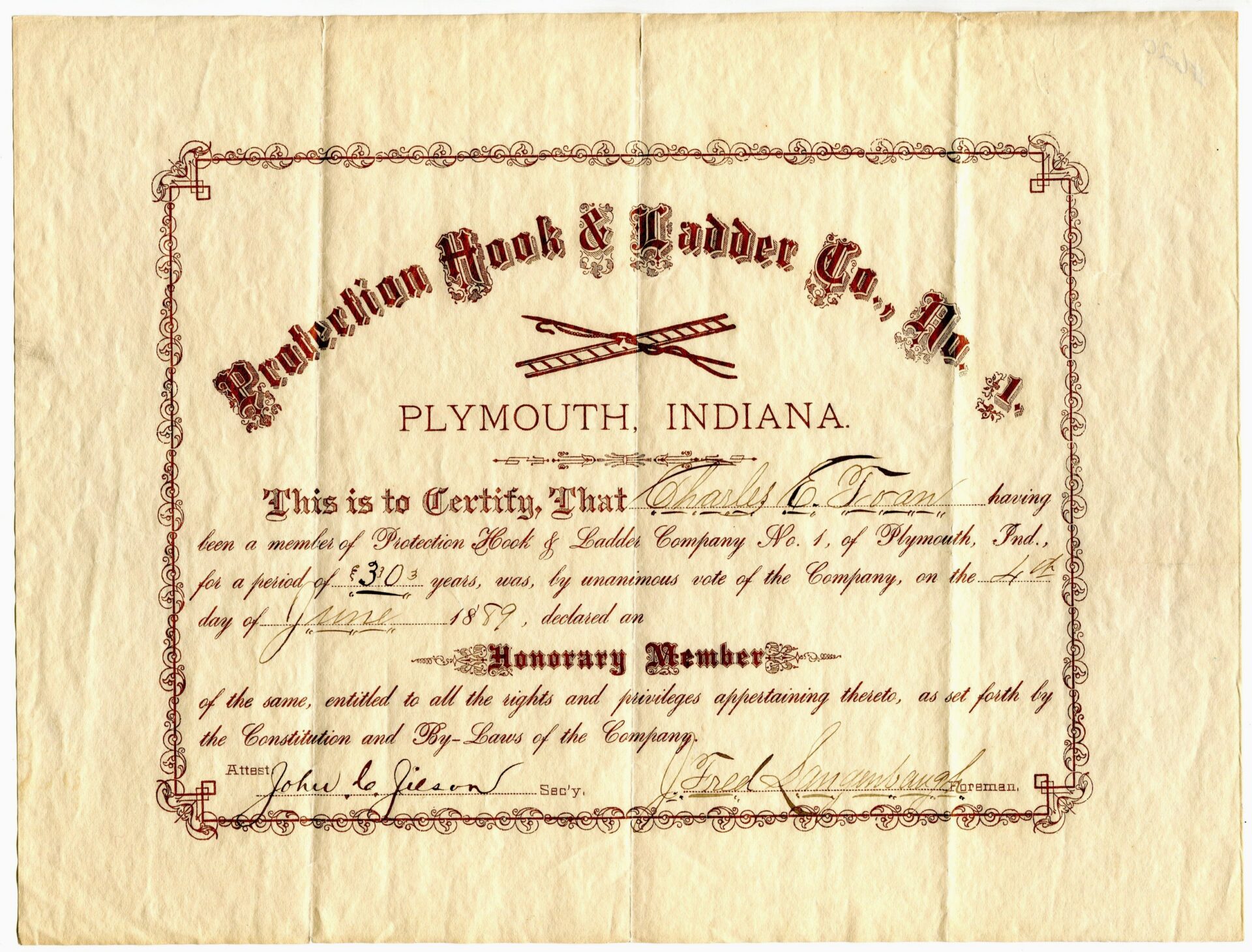

Feature Image. From left: Betty Jane Smith; Mildred Isom, Betty Jane Smith, and Eleanor Turner (photo courtesy Mildred Isom)

By: By Mildred Isom, Edited by Jeff Kenney and Anita Boetsma

In July 2007, Mildred Isom, originally of Culver, sent an essay about her recollections of her friendship with — and subsequent grief at the death of — Betty Jane Smith, one of the four African American children drowned in the 1947 tragedy. Betty Jane was buried in Mildred’s band uniform, a fact which Mildred blocked from memory.

Betty Jane Smith was a member of our exclusive quartet of friends at Culver High School. She was an orphan who came from Chicago to live with her grandparents in our little farm town of Culver, IN, in the early 1940’s. The four of us were immediately drawn together into the same activities with the same goals. Marching Band, softball and other sports were our first choices but we soon we all joined Chapel Choir and the orchestra. Our band and sports teams went out of town each year to compete in contests statewide.

Betty Jane Smith.

Betty’s bubbly personality kept us all cheerful, and her long black sausage curls were natural. Never before and never after have I been a part of such a fun loving, loyal and hardworking group. Before long Betty’s cousins, Eleanor, Winston and Paul, arrived to live with the grandparents. Their parents were professionals in Chicago, a dentist, doctor and podiatrist. I did not even know what a podiatrist was at that time. Betty’s grandmother’s name was Augusta, but we all called her Ga Ga because the little ones could not pronounce her name. The grandfather was Lloyd Smith, a rotund, jolly white-haired gentleman who kidded us for our attempts at cooking but never failed to consume it. This family was one of the only two black families in our town and were not related. In Plymouth, a mere 10 miles north, blacks were not allowed in town after 6:00 pm. This was a mystery to us in our teenage years in the mid-1940s.*

More time was spent at Betty Jane’s house than mine. I was always invited for Friday night sleepovers, Sunday dinners and holidays. My mother had passed away many years before, my older sister was married, and my father worked long hours and was seldom home. Betty Jane, although much loved and always cheerful, still I think, felt like an orphan and basically so did I at the time. We were a comfort to each other and felt like sisters. During the summers one or more of the quartet joined us in swimming, fishing, bike riding and any kind of sports, music and babysitting.

On Friday nights during the summer, we usually rode our bikes around the north side of Lake Maxinkuckee to attend the free movies offered by the Culver Military Academy. During the winters we walked directly across the lake which was frozen over three months of the year. One Friday night I had the flu and did not go with them. About 8:30 p.m. my father came home and told me that he and two friends had pulled Betty Jane, Winston and Paul from the lake. They had fallen through a thin spot in the ice. Betty Jane’s cousin, Eleanor Turner, was the only survivor. Eleanor said that her brother, Winston Turner, had lifted and pushed her up onto solid ice before he succumbed. She was able to retrace her steps back to the starting point. Although my father was gentle in telling me, I doubt if he really ever knew how it affected me. My only real confidant at that time was Betty Jane’s grandmother. I remember visiting her once right after the event. We experienced tears, hugs and holding each other. As far as I remember, I never went back. I could never bear to again step into the house. This occurred when we were in the 8th grade.

Life went on, of course. Eleanor continued high school with us but we did not become any closer as she was the studious one and being chubby all her life, she did not care for sports. She did continue to be in the marching band. At our class reunion in 2001, she wrote saying she was married, living in New York and regretted she would not be able to attend the reunion.

After the reunion banquet, three of us left in the quartet met at Helen Sikora Zalas’ house, my longtime girlfriend’s, in South Bend, to carry on with our own reunion. After rehashing and chuckling about a lot of past incidents, Betty Jane’s name was brought up. Helen turned to me and said, “That was really nice of you to let them use your band uniform for Betty to be buried in.” I said something like “huh?” Then the other two girls told me the Band Director had asked if I would donate my uniform and I had said yes, so they transferred my medals onto a maroon cardigan sweater. Helen asked if I remembered going to the services. I had to say “no.” I was told we all marched fully uniformed down Main Street to the Evangelical Church for services and further to the cemetery. One of the girls said that the band director accumulated enough funds to purchase a new uniform jacket for me about a year later. I had no recollection of these events at the time and still do not.

As the years go by I still think of Betty Jane, and the way we were a long time ago.

*Editor’s Note: According to the Encyclopedia Britannica and other online resources, ”Sundown Towns” excluded people of color from being in town after sunset. This practice existed across the U.S. during the 20th Century.

The Museum is home to many stories like this one. Information about the history of Black communities in Culver is available as well. The Museum is open from 10 until 4 from Tuesday through Saturday at 123 N. Michigan St., Plymouth. For more information, call 574-936-2306.