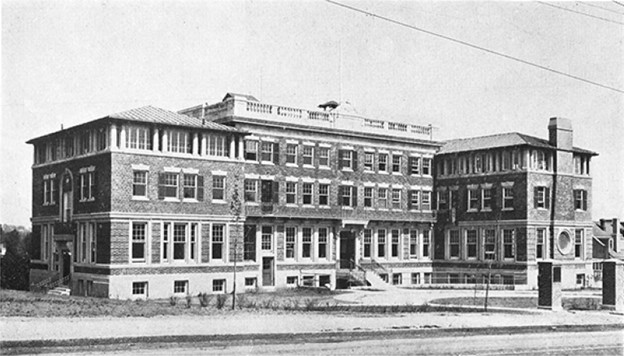

In 1892, Plymouth was a stop for an “orphan train” that transported thousands of children. They came from the streets of New York and New England to new homes in the Midwest. From 1854-1929, nearly 4,000 orphans, ranging from ages 1 to 12 were brought to Indiana. All together almost 250,000 “little waifs” climbed aboard the orphan trains and headed west in search of a family. They got off the train with name cards pinned to their clothing. Many were orphaned not only by the death of a parent, but because of poverty and neglect, and would have died on the streets. The image above features the New England Home for Little Wanderers of Boston. Rev. H.S. Kimball, an agent of the home, preaches at the M.E. Church in Argos.

Who Took In Travelers from the Orphan Train?

Children from the orphan trains were placed in homes depending on the needs of prospective adoptive parents. Sometimes their own child had died and they were seeking to expand their family. Some older couples needed someone to look after them, or a farm family needed an extra pair of hands to help with the chores. Some of the agricultural families believed the abandoned children should work to “earn their keep.” Sadly, some siblings went to different homes. The orphans were at the mercy of their adoptive families.

Locally, 26 orphans found permanent homes in Marshall County from the New England Orphan’s Home, although the supply didn’t meet the demand for these kids. “The children were the objects of considerable attention,” according to an edition of the June 1892 Plymouth Democrat. The orphans, gathered at the Methodist church in Plymouth, hoped to win the hearts of a new family. The would-be foster parents could specify exactly what they wanted. For instance, a blue-eyed blonde female, or a sturdy red-headed male. Some orphans were luckier than others. Many were placed loving homes with caring families, but others lived a life of hard farm labor. It seemed a bit callous, but “beggars couldn’t be choosers.” Although every situation was unique, adoption was perceived as better than life on the streets.

The Good and the Bad of Adoption

One of the grown-up orphans that made her home in another state, Jesse Martin, said that being an orphan train rider taught her to have more understanding of people’s pain. She never felt like she fit in. She said the children at school would say, “No one cares for you, not even your own mother!” She says she simply became grateful for the kind people along the way.

Not all these little wanderers had such an unhappy experience. Many found good homes and received the best of care. One particular child caught the eye of a new parent that was grieving from the loss of their own. According to an article from the 1990 Herald Banner, (Greenville, Texas) Helen Hale Vaughn said that her mother would become very angry at anyone who referred to her as their “adoptive” daughter. Whenever Helen would come home broken-hearted, her mother would embrace her and say, “You just remember, we chose you, and they were born to their parents, so they had to have ’em!”

The Legacy of the Orphan Train and Its Travelers

Some of the orphans given an opportunity for a new life prospered and flourished in their new environment. Many orphan train children went on to live long productive lives and were able to enjoy their grandchildren, and many times great-grandchildren. They weren’t looking for fame and fortune, but a better life and “to love and be loved!” The orphan train provided a means for these children to have the will to go on and made survivors out of them.

For more specific information on the local impact of the orphan train, visit the Marshall County Museum and enjoy the research done by Christopher Chalko who spent time collecting data, newspaper articles and personal letters of people that actually rode the orphan train. It’s interesting reading material that is a part of our history in Marshall County and across the United States.